Logical Conditional

The logical conditional, also known as implication, is a logical connective that links two propositions to form a new one, stating that if the first is true, then the second must also be true. It is formally symbolized as p → q and is read "if p, then q”; in this structure, p is called the antecedent (the condition), while q is the consequent (the result).

What defines the conditional is that it is false in only one case: when the antecedent is true and the consequent is false; in all other combinations of truth values, the implication is considered true. This rule implies an important peculiarity: if the antecedent is false, the conditional is true regardless of the consequent's value. Although this behavior may seem counterintuitive in everyday language, it is fundamental to the coherence of formal logic.

Let's look at some examples to clarify how it works in practice:

- "If you study, then you pass": this proposition would only be false in one case: if you study (p is true) and you do not pass (q is false). If you do not study, the original promise is not broken, regardless of whether you pass or not.

- "If it rains, then the street gets wet": this statement is false only if it is raining and yet the street remains dry. If it does not rain, the implication remains true, regardless of whether the street is wet for another reason (like a cleaning truck).

- "If 2 + 2 = 5, then the sky is blue": although there is no relationship between the two ideas, from a logical standpoint, the implication is true because the antecedent is false. Logic does not judge the content, only the combination of truth values.

Table of Contents

Truth table

The fundamental rule of the conditional is simple: p → q is false only when p is true and q is false. In all other cases, the implication is true. This behavior becomes clear when reviewing its truth table:

| p | q | p → q |

|---|---|---|

| T | T | T |

| T | F | F |

| F | T | T |

| F | F | T |

Let's analyze each case:

- If p is true and q is true, the implication holds (true).

- If p is true but q is false, the implication does not hold (false).

- If p is false, the value of q does not matter: the implication is considered true by default.

A useful way to understand the conditional is to interpret it as a promise: the only way to break it is for the antecedent to be met and the consequent not. For example, if we say "if you pass the exam, I will give you a book," the promise is only broken if you pass the exam but do not receive the book. If you do not pass, the promise remains intact and unbroken, regardless of whether you are given the book or not.

This logical peculiarity explains why a statement like "if 2 + 2 = 5, then there is life on Mars" is considered formally true: since the antecedent is false, the "promise" is not broken, so the implication holds regardless of the truth of the consequent.

There are different ways to read the expression p → q; the most common are:

- If p, then q.

- p implies q.

- p is sufficient for q.

- q is necessary for p.

Associated Implications

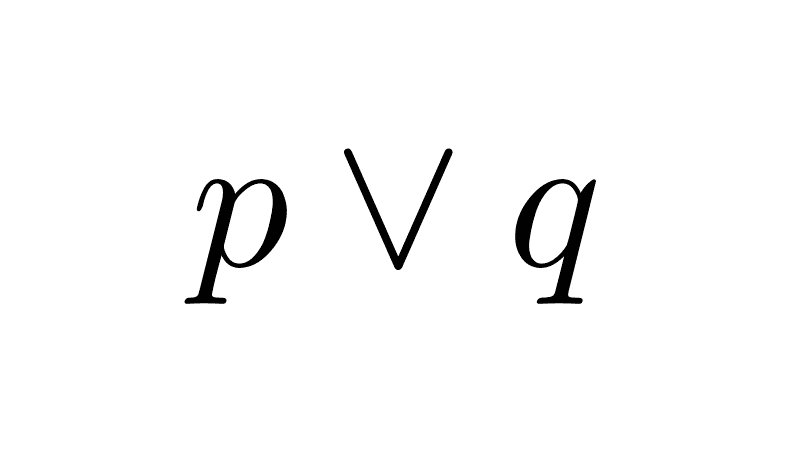

From a direct implication p → q, we can define three logical variants that help us analyze the relationship from different perspectives:

1) Converse: q → p

Here we swap the antecedent and consequent. For example, if the original proposition is "if it rains, the street gets wet," the converse would be "if the street is wet, then it is raining."

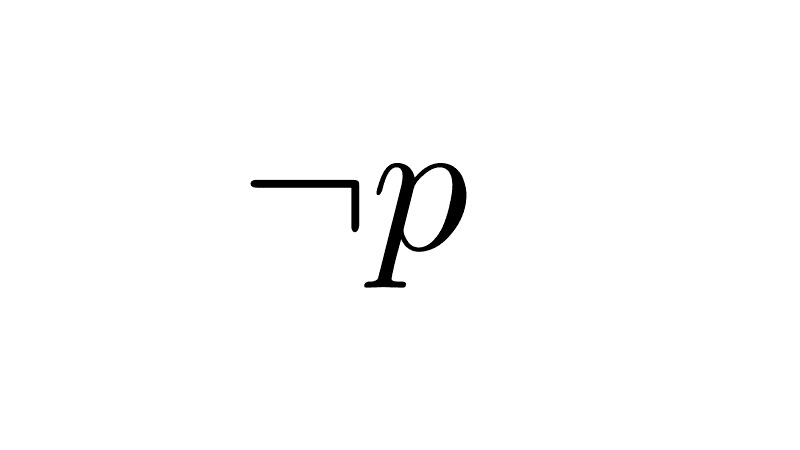

2) Inverse: ¬p → ¬q

In this case, we negate both propositions while keeping the original order. With the previous example, the inverse is "if it does not rain, then the street does not get wet."

3) Contrapositive: ¬q → ¬p

In this case, we negate both propositions and swap them. With our example, it would be “if the street is not wet, then it is not raining.”

One of the most important properties of the conditional is that every implication is logically equivalent to its contrapositive. That is:

p → q ≡ ¬q → ¬p

This can be proven with a truth table by observing that both compound propositions have the same truth value for every possible interpretation.

| p | q | ¬p | ¬q | p → q | ¬q → ¬p | p → q ≡ ¬q → ¬p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | F | F | T | T | T |

| T | F | F | T | F | F | T |

| F | T | T | F | T | T | T |

| F | F | T | T | T | T | T |

It is important to note that neither the converse nor the inverse are equivalent to the original implication. Returning to our example:

- The converse "if the street is wet, then it is raining" can be false (the street could be wet for other reasons).

- The inverse "if it does not rain, then the street does not get wet" can also be false (the street could have been watered).

Properties

The simple conditional has several fundamental properties that allow for the manipulation and simplification of expressions in propositional logic. Below are the most relevant ones:

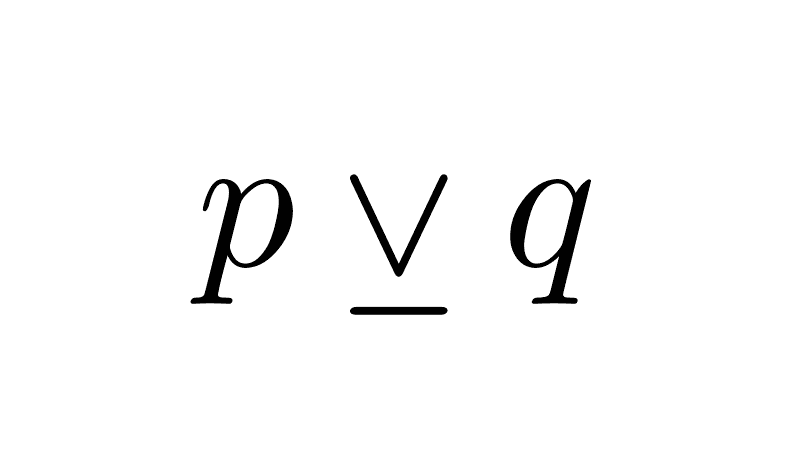

1) Equivalence as disjunction: One of the most useful transformations is expressing the implication as a disjunction as follows:

p → q ≡ ¬p ∨ q

This equivalence is frequently used to simplify proofs and logical analyses. We can confirm it is true by creating a truth table:

| p | q | ¬p | p → q | ¬p ∨ q | p → q ≡ ¬p ∨ q |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | T | F | T | T | T |

| T | F | F | F | F | T |

| F | T | T | T | T | T |

| F | F | T | T | T | T |

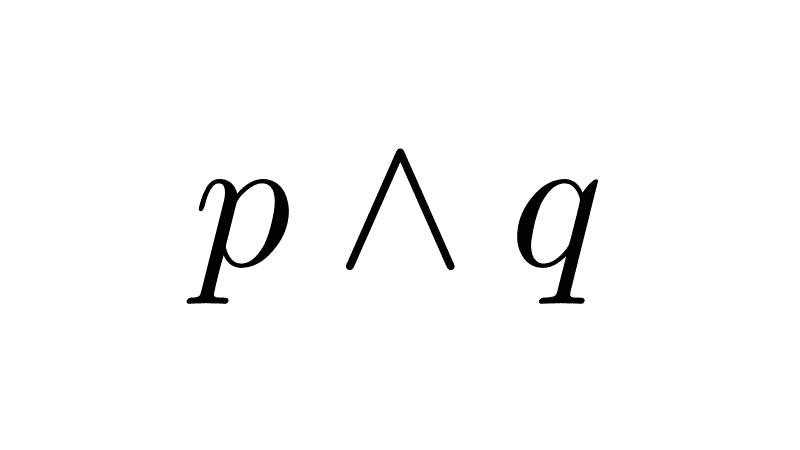

2) Negation of an implication: To negate a conditional, we apply the following equivalence:

¬(p → q) ≡ p ∧ ¬q

This confirms that the only way to falsify "if p then q" is when p is true and q is false.

3) Contrapositive: As mentioned earlier, every implication is equivalent to its contrapositive:

p → q ≡ ¬q → ¬p

This property is fundamental in indirect mathematical proofs.

4) Transitivity (hypothetical syllogism): If one condition implies a second, and that second in turn implies a third, then the first implies the third:

[ (p → q) ∧ (q → r) ] → (p → r)

5) Modus Ponens: This is a rule of inference that allows us to affirm the consequent when the antecedent is met:

[ (p → q) ∧ p ] → q

6) Modus Tollens: If an implication is true but its consequent is false, then the antecedent must also be false:

[ (p → q) ∧ ¬q ] → ¬p

6) Exportation-Importation: This rule allows us to rewrite consecutive implications as a single expression:

(p ∧ q → r) ≡ (p → (q → r))

7) Reductio ad absurdum: If assuming p leads to both q and ¬q, then p must be false:

(p → q) ∧ (p → ¬q) ≡ ¬p

This technique is widely used in proving theorems.

8) Relationship with tautologies and contradictions: Let T be a tautology (a proposition that is always true) and F be a contradiction (a proposition that is always false), then:

p → T ≡ T

p → F ≡ ¬p

T → p ≡ p

F → p ≡ T

Unlike other connectives, implication does not satisfy certain properties:

- It is not commutative: p → q is not equivalent to q → p.

- It is not idempotent: p → p ≡ T, but it does not reduce to p.

- It is not associative in the traditional sense like other operators.

Conditionals in mathematical theorems

The "if..., then..." structure is the basis for most mathematical theorems, where a relationship is established between a hypothesis (initial condition) and a conclusion (the derived result). This formulation guarantees that whenever the hypothesis is met, the conclusion must necessarily follow.

Example: "if a number is divisible by 4, then it is even"

Let's analyze different cases:

1) Hypothesis and conclusion are met:

Let's take the number 8. It is divisible by 4 (true hypothesis) and is indeed even (true conclusion). The theorem holds.

2) Hypothesis is met but the conclusion is NOT:

Is there any number divisible by 4 that is not even? No, because every multiple of 4 is also a multiple of 2. This case does not exist, which confirms the theorem's validity.

3) Hypothesis is NOT met but the conclusion IS:

Consider the number 6. It is not divisible by 4 (false hypothesis), but it is even (true conclusion). The theorem remains valid because it only guarantees something when the hypothesis is met. In other words, if the hypothesis is not met, anything can happen with the conclusion, and the theorem will still be valid.

4) NEITHER hypothesis NOR conclusion is met:

The number 5 is not divisible by 4 (false hypothesis) and is not even either (false conclusion). The theorem remains valid as it requires nothing when the hypothesis is false.

It is important to understand that the theorem "if a number is divisible by 4, then it is even" does not claim that all even numbers are divisible by 4 (that would be the converse, which is false). It only establishes a specific direction: divisibility by 4 is a sufficient condition for being even.

Using the contrapositive is particularly useful in proving theorems since, as we have seen, p → q ≡ ¬q → ¬p. This means that instead of directly proving that “if the hypothesis holds, then the conclusion follows,” we can prove that “if the conclusion does not follow, then the hypothesis does not hold.” Both statements are logically equivalent, so proving one is equivalent to proving the other.

In the previous example, the contrapositive of the theorem “if a number is divisible by 4, then it is even” would be: “if a number is not even, then it is not divisible by 4.” This formulation is often easier to verify: if a number is odd, it clearly cannot be divisible by 4. Thus, by proving the contrapositive, we have also demonstrated the validity of the original theorem. This technique is frequently used when a direct proof is more complicated or less intuitive.

Did you find this useful? Rate it!

Leave a Reply

Related posts